The soulfulness of our denim

What is it about our jeans that gives us that precious sense of their having a soul?

As touched on in the homepage, it’s the way your jeans evolve- with the life of the wearer- ripening and maturing with age and wear, but specific to that individual (or at least in a way that feels specific) - moulding to the wearer’s gait, movement, personality, lifestyle.

Engaging in a dialogue with the wearer, the jeans are quietly doing what they can to assist, aid and abet the wearer in living their best life (sartorially).

No doubt in fact it is the very nature of denim that it looks better worn, aged, and ripened. Whatever happens, denim softens and improves with age, and the way it matures is [necessarily] consequent to the life of the wearer- it is the wearer who is exerting pressure on the denim to age, ripen and mature it. On the other hand this idea gets turned around and spun into the myth of the jeans doing the work on behalf of- or at least in cahoots with- the wearer, that there is some kind of symbiosis going on, which is most likely an exaggeration. And it’s in the very nature of the fabric that it softens, creases, tears and fades, characterfully almost however badly (or well) it’s treated. Denim is a resilient but also a supple fabric that almost needs to be weathered or beaten up to start looking- and performing to- its best.

It also follows that some denims can create a greater and more precious sense of having a soul than others, to do with how characterful and beautiful they are to begin with, then how characterfully and beautifully they age- soften, fade and develop texture- and then also how durable they are, how long they last, longevity enabling a better realisation of their ageing potential.

Usually the key and defining variables here are (a) the length of the individual fibres (i.e. whether the cotton is long or short staple cotton), and secondly- and crucially- (b) the way the yarn is spun, then dyed, and then woven.

Different types of cotton

Long staple cotton, where the length of the individual fibers is between 1 1/2” - 2 1/2”, is softer, silkier, and more durable than short staple cotton (say where the length of the fibers are 1” long).

Long staple cotton is sought after but also significantly more expensive to cultivate and in shorter supply.

Mass produced denim uses short staple cotton, with long staple cotton usually reserved for the higher bracket within premium denim.

Next let’s take a look at the second set of key variables in denim, its grade and complexity, that generates that precious sense of your jeans have a soul, namely the spinning, and then the dyeing, and then the weaving of the yarn.

The Spinning: Ring-Spinning

There are two industrial methods today of spinning raw (carded) cotton to make the thread that then gets dyed and woven into denim fabric.

Ring-spinning is the traditional method, which is the way cotton yarn was spun from pre-historic times right through to the 1980s.

Ring-spinning started off as a manual process using spindles, the individual cotton fibers roll-twisted into yarn on spindles rotated by hand, and was successively semi-automated via innovations such as the Spinning Wheel, to the Spinning Jenny, to the Throstle Frame, to Arkwright’s Water Frame (of 1765), and then fully automated via the Ring Frame of 1829, with successive upgrades to the Ring Frame continuing through the decades (and century) right up to the 1970s and beyond—- all of which were based on the same basic principle of spinning the thread by roll-twisting the fibres into yarn via rotating spindles.

Rotary, or open-end, spinning was innovated and commercialised in the late 1970s to early 1980s, and by the mid-’80s industry-wide method for spinning cotton yarn for mass-produced denim globally.

Rotary or open-end spinning could deliver yarn 7-9 times faster than ring-spinning, and was also significantly cheaper.

In ring-spinning the fibres are rolled into shape by being wound around a rotating spindle, whereas in open end (rotary) spinning the fibres are air-twisted and effectively pressed into shape through a centrifugal action, by currents.

Ring-spinning produces a stronger, more compact yarn, and - in addition to its higher durability and tensile strength - a far softer and silkier hand.

Ring spinning also introduces ‘slubs’- natural imperfections created through the process, that in denim give it what is deemed character and beauty and- keenly- an ‘authentic, vintage denim’ look in terms of appearance.

Open-end denim tends to have a more open, fuzzier appearance and a coarser hand.

And it’s in the spinning, this is the real key to creating beautiful and ageing worthy denim.

So with the industry-wide change in the spinning (to open-end) in the mid-1980s, it was now a different kind of denim that was being produced and distributed into the global marketplace, with effectively a change in its core or you could say molecular structure.

The strongest, most beautiful denim is dual-ring-spun (aka “ring x ring” denim), where both the warp and weft yarns are ring-spun.

Vis a vis the mass produced denim you get today which is either

(a) open end (rotary spun);

or (b) ring-spun where just the weft yarn is ring-spun and the warp is open end.

The consequences of this [in the ‘80s] weren’t quite understood or forseen by the consumer or even the industry at the time, and still today it remains a big question or mystery to many, although the frustrations - and the reverence (for vintage) - is very much there.

Dual-ring-spun- and therefore in my view truly ‘soulful’- denim can be sourced today but via only a handful of Japanese mills, and one or two in Italy. Likewise is only really available to the consumer today within the higher brackets of premium denim.

________________________________________

Ring-Spinning: the Spinning Wheel, an early example of

Spinning Jenny - as in James Hargreaves’ Spinning Jenny (for spinning the raw cotton into thread), patented in 1770

Ring-Spinning: Richard Arkwright’s Water Frame, as first used in 1765. Patented in 1769

Originally powered by waterwheels (and horses).

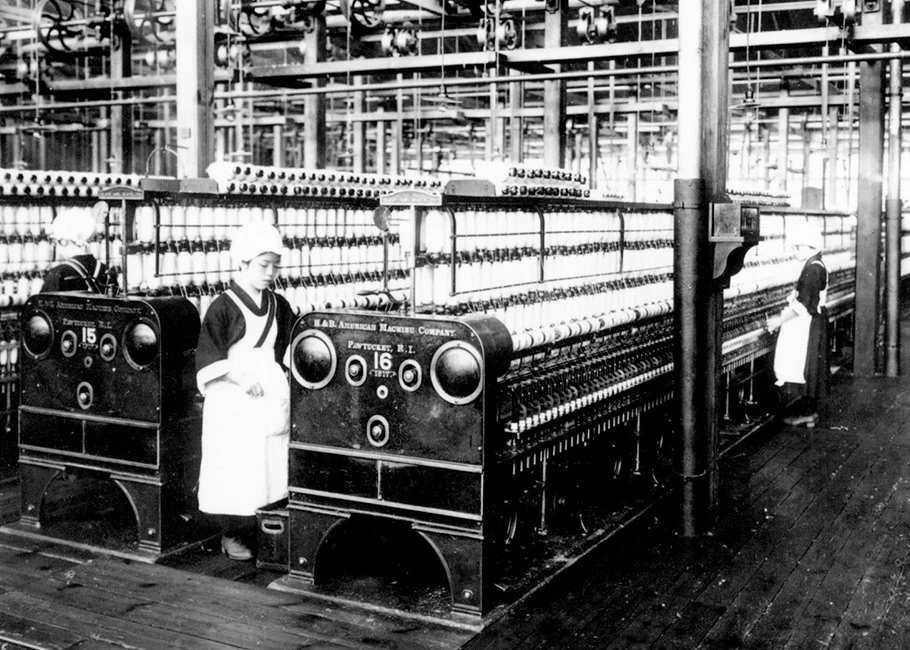

Ring-Spinning - the Ring Frame (for spinning the raw cotton into cotton thread), as invented in 1829 and credited to John Thorpe of Rhode Island, Massachusetts USA

Ring-Frame (for ring spinning the raw cotton into cotton thread), 1920s

Ring-Spinning: the Ring-Frame at Kurabo Mills, Japan. Circa 1915

Ring-Spinning - modern Ring Frame for higher production, circa 1980

Open End Spinning: A modern day rotor open-end spinning machine

Open End Spinning: Titan, TQF 368, Rotor Open End Spinning Machine

________________________________________

The Dyeing: Rope dyeing

In 1915 Rope-dyeing was automated and established- a kind of next stage progression of hank or skein dyeing (the go-to method of dyeing denim since the 1500s).

It was based on similar principles, as hank or skein dyeing, of dipping bundles of yarn (now ropes) into successive dye baths, followed by skying (oxidation) after each dip.

Only with the ropes you now got the bonus of a ‘ring-dye’ effect (varying degrees of penetration of the dye where the surface area of the ropes is more- or less- exposed).

This ‘ring-dye’ effect that you get from rope-dyeing is now sought after today for its quirky, dynamic and a kind of multi-dimensional finished look it gives to the dyed yarn, another factor which contributes to rope-dyed denim having that precious sense of ‘soul’.

Rope-dyeing, since replaced (again around the mid-’80s) by the 7-9 times faster and cheaper ‘slasher’ or ‘sheet’ dyeing, also introduces a greater sense of depth to the weave, as well as a deeper, richer hue and better fade characteristics (as compared to the modern day slasher or sheet dyeing method).

The modern day “slasher” or “sheet” dyeing, which replaced rope-dyeing industry-wide in the 1980s, involves beaming the yarn onto large sheets, then dipping the sheets into successive dye baths.

This process creates a more basic, uniform, even look to the dyed yarn- without the “ring dye'“ effect, or depth of hue and richness of caste that you achieve with the ropes. And crucially - and this is again the key- the modern day slasher or sheet dyeing results in a less characterful fade propensity to the dyed fabric.

So, other than in the spinning (ring-spinning) the key to creating characterful, soulful denim is in the dyeing- rope-dyeing.

And while rope-dyeing was the go-to method of dyeing denim throughout the industry, globally right up to the mid 1980s, to repeat - the modern day slasher or sheet dyeing is what virtually the whole industry switched to, globally, in the 1980s- and rope-dyeing is today maintained by only a handful of premium denim mills in Japan, and one or two Italy, and only generally available within premium denim.

Hank dyeing, an example of

An indigo dyed hank of yarn

Skein dyeing (6 skeins = 1 hank)

Skeins of yarn dyed indigo with different levels of saturation (no’s of dips)

An industrial rope-dyeing plant, circa 1980

Rope-dyed yarn

A modern day indigo slasher (or sheet) dyeing plant

________________________________________

The Weaving – the vintage Shuttle loom vs. the modern day Projectile loom

As to differences in the weaving, between then (pre-1980s) and now, which is where some denim heads take particular pride, this isn’t truthfully the same sine-qua-non for exquisite looking, core-integrity characterful and soulful denim as is the spinning or the dyeing, but it’s a key signal for some as to its probable construction:

namely that denim purposely set aside and elected to be woven on vintage shuttle looms today- shuttle looms being old-school traditional, more expensive, slower and less productive weaving machines- is most likely also dual-ring-spun and rope dyed.

That said however, due to the current day fascination with ‘selvedge’- ‘selvedge’ being the clean ‘self-edge’ that you get when the fabric is woven on vintage shuttle-looms- and selvedge being highly sought after in itself today (albeit that was originally to do with its associations with being dual-ring-spun and rope-dyed), some manufacturers are using vintage shuttle looms to produce selvedge denim which at its core is spun as open-end and is not rope-dyed either.

__________

Shuttle loom weaving, namely the flying shuttle loom, was invented and patented by John Kay in 1733, which increased the efficiency of weaving several times over from the hand loom.

From then on shuttle loom weaving became the industry-wide adopted method for weaving denim, and In 1894 the first fully automated shuttle loom was introduced, by the Draper Corporation, in the US.

The Draper’s automatic loom, known as “The Northrop”, became a huge success in the US and by 1914 Northrops made up 40% of looms in American mills.

Picanol from Belgium and Toyoda from Japan (the precursor of today’s Toyota Motor Corporation) also made competing, fully automated shuttle looms, but it was the Draper that was most recognised and adopted in the US.

While weaving on a shuttle loom is slow (5-6 times slower) compared to the larger format shuttle-less Projectile looms of today, the vast majority of US denim right up to the end of the 1970s was woven on Draper shuttle looms. It was only in 1985 that Cone Mills, the then main denim supplier to Levis, Wrangler and Lee, replaced all of its Draper X3 shuttle looms with the larger format Swiss Sulzer (Projectile) looms.

Shuttle loom design is today loved for its aesthetics- the lower tension on the yarn, due to its lower speed, as compared to the super-speed modern day Projectile looms- weaves denim in such a way that it subsequently fades more beautifully, and the loom also tolerates more slubs (those prized characterful imperfections within the dual-ring-spun yarn that it would have normally been fed with).

The sheer weight and momentum of the 40cm long shuttle crossing the 30” wide shed of warp threads (of the weaving frame) back and forth in a zig-zag at three times per second, against the clunky, heavy machinery of the loom, then brings on its own intern or shudder, known as ‘loom chatter’- introducing its own unique rhythm, mood swings or you could say fingerprint- or ‘soul’- into the woven fabric.

And whereas this characteristic in other fabrics would be passed off as an error, as imperfections, in denim it would only add to the beauty (and the sense of depth and dimension, or ‘soul’), at the same time impossible to replicate.

The single- unbroken- weft thread that is being interlaced in a shuttle loom, back and forth, through the warp yarn, battened down at either end, gives a clean woven edge to the fabric known as a ‘self-edge’, or ‘selvedge’ or ‘selvage’.

And so, selvedge has become synonymous with denim woven on shuttle looms vis a vis the vulnerable raw edge that’s created on the larger format Projectile looms of today, where weft the thread is cut and then re-inserted each time on its crosswise journey through the warp.

So, to repeat, virtually all denim globally right up to the end of the 1970s was woven on shuttle looms and self-edged (which also accounts for the then popularity of cuffed denim).

Then, ever since the 1980s, the speed of weaving from around 140 to 160 picks per minute on shuttle looms was multiplied several times over to around 400-600 picks per minute on the newer larger format Projectile (shuttle-less) looms. And these larger format Projectile looms were adopted more or less industry-wide, globally, except again for a handful of premium denim mills in Japan, Italy and the US. At the same time, with these Projectile looms the width of the weaving frame (and hence of the fabric) was also doubled from 30” to 60” or wider still- now that no longer was there a heavy shuttle that had to be propelled back and forth across the width of the frame.

Basic hand loom (for weaving the spun yarn into fabric) - as used circa 17th century

Manually operated flying shuttle loom (for weaving the spun yarn into fabric) - as invented by John Kay in 1733

Manually operated flying shuttle loom (for weaving the spun yarn into fabric) - as used in industry circa 1750 to 1850

Fully automated flying shuttle loom (for weaving the spun yarn into fabric), as first developed by the Draper Corporation in 1894.

Cone Denim’s DRAPER X3 shuttle looms, at their White Oak facility in Greensboro, North Carolina USA (circa 2017)

________________________________________

It is also true however that around the same time, from the 1980s onwards select Japanese mills came forward and experimented with techniques based on the old school method (ring-spinning, and rope-dyeing - which were the real key - and then also shuttle-loom weaving, which is for some “denim heads” the final part of the true equation for expert characterful and truly soulful denim)- and they began to push the limits of what denim is, beyond that of the heritage.

These select Japanese mills created in the ‘90s and through the 2000s (and still are creating, to the present day) heavier, more slubby, softer, silkier, more exquisite, more beautiful, more hard-wearing and more soulful denim than ever before, albeit at price points that would exclude all but the higher bracket of the premium denim heirarchy.

The myth about Japan

It is also true that Japan scooped up many of the old American Draper shuttle looms when the American mills re-automated to the (shuttle-less) Projectile looms. But it is also a bit of a myth that Japan’s success in this area is down to their having purchased the old Draper looms.

- The vast majority of shuttle looms in Japan are Toyoda (the precursor of the Toyota Motor Corporation).

There is a Draper on display at the Evisu store in Tokyo, owned by Hidehiko Yamane, the man who created the myth-

possibly to romanticise Japanese denim heritage with a bit of Americana, in order to help sell jeans.

The Vidalia Mills, Louisiana

Romanticism around selvedge continues to grow in the US.

46 of the 51 Cone Mill’s White Oak Plant Draper X3 shuttle looms having been bought up in 2018 (after the closure of White Oak in 2017) by the Vidalia Mills in Louisiana, and the remaining 4 by the Huston Textile Co in Sacramento, California.

Vidalia even went to the extent of importing in White Oak’s (Cone Mills’) wooden floors to replicate the shudder and resulting ‘loom chatter’– and resulting ‘fingerprint’ or ‘soul’ arising from the mood swings of the clunky wooden shuttle moving at vast speed against the weighty, clunky machine- although weavers discovered that placing rubber footings under the looms preserved their quirky shudders and shakes just fine.

The first of the Cone Mills’ Draper X3 Shuttle Looms re-housed at the Vidalia Mills in Louisiana in 2018

A Sakamoto Shuttle Loom, Japan. circa 2015

________________________________________